Where does our water come from?

Most of Arizona is a desert landscape. Dry plains and mountains are dotted with cacti, ocotillo, and other drought resilient plants. Despite Arizona’s natural aridity, in the urban areas pools glisten in backyards, parks and golf courses are miraculously green, and water flows plentifully from household appliances. Where is all this water coming from?

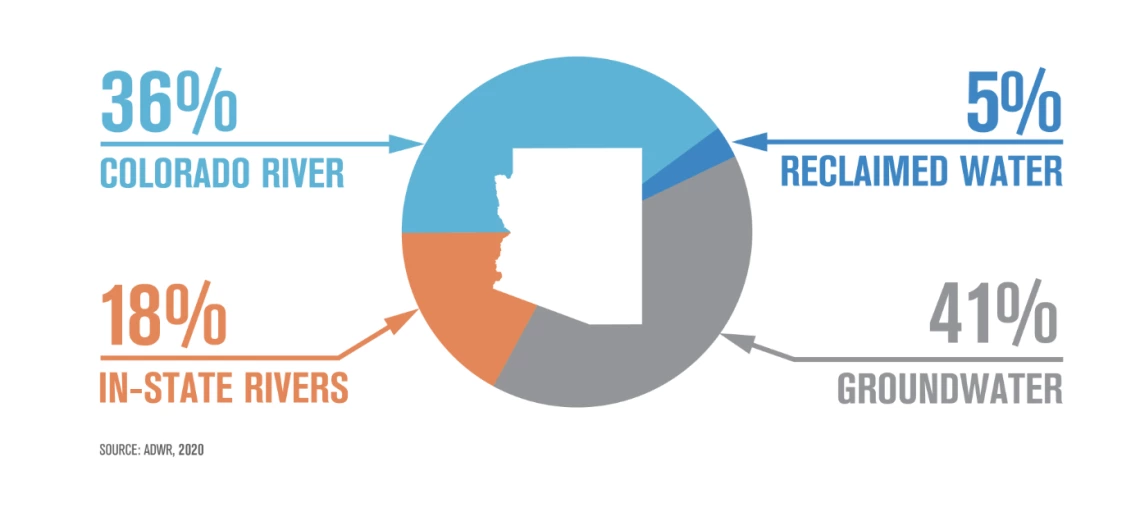

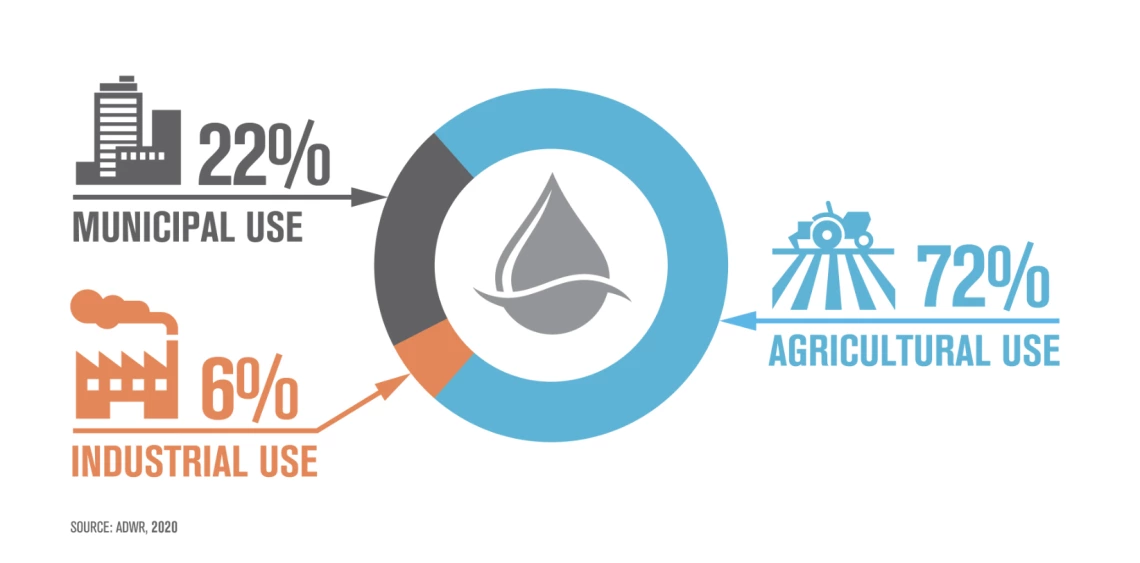

Arizona has more water than is obvious at first glance, but a lot of it is underground. 41% of Arizona’s water comes from groundwater. However, the state would still not be able to support its growing population without the Colorado River. The river supports 36% of the state's water use. The rest of Arizona’s water comes from 18% in-state rivers and 5% reclaimed water. The majority of this water (72%) supports agriculture, 22% goes to towns and cities, and the remaining 6% is used by industrial facilities (5).

How the Water System Works

The water that flows from your faucet undergoes a journey to reach you. Water from groundwater or surface water is filtered by a water treatment or purification plant so that it meets CWA (Clean Water Act) and SDWA (Safe Drinking Water Act) standards. This process involves killing bacteria and removing harmful chemicals. This is the water that comes out of your tap that you use to shower, fill your cup, wash your hands and cook with.

After the water goes down the drain, it is funneled to a different facility called a wastewater treatment plant. This facility also filters the water to remove bacteria and harmful chemicals, but to less strict standards than the drinking water standards. Then the water is discharged into surface bodies of water like a lake or river, or funneled back into aquifers.

Groundwater: Our Largest Source of Water

At 41%, the largest source of Arizona’s water is groundwater (5). When you look around the desert the surface may be dry, but there are reservoirs of water hiding underground.

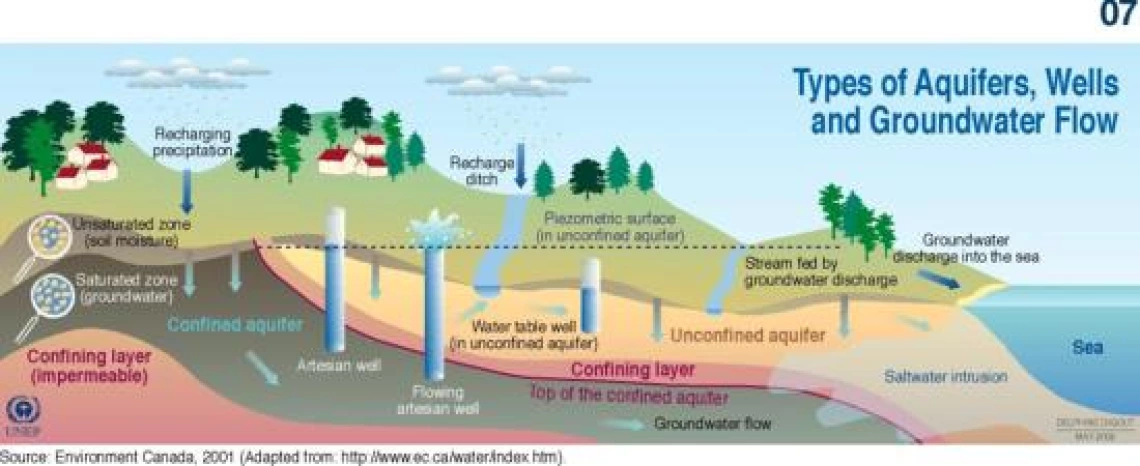

Groundwater is water that seeps down through the soil after it rains. It is collected and held in cracks and spaces in rock and sediment. These bodies of rock that hold the groundwater are called aquifers (6). It takes a long time for water to seep through the ground so aquifers are not refilled as quickly as a river or lake would be after a rainstorm.

Gridarendal, 2005 (12)

In the first episode of Making Arizona, Jacelle Ramon-Sauberan explains how in the early 20th century non-indigenous farmers and miners in Tucson were draining the local aquifer faster than it could naturally refill. The depletion of groundwater dried up the Santa Cruz river and challenged the Tohono O’odham tribe’s access to water.

The tribe and the city of Tucson eventually received access to Colorado River water. Now Tucson is using Colorado River water to refill the aquifers, and reclaimed water to restore the Santa Cruz (8).

Colorado River Water: An Important Contributor Facing Challenges

36% of water that Arizona uses comes from the Colorado River (5). To deliver river water to major Arizona cities, a canal called the Central Arizona Project (CAP) was built in the 1980s. Unfortunately the Colorado River is dealing with unprecedented shortages due to a combined effect of climate change, the southwestern megadrought, and overuse. It was legally divided between tribes and seven states under the assumption it would provide 17 million acre feet per year, but the river flow is now about 12 million acre feet (11). Cities receiving water from CAP are newer users of the Colorado River water, so places like Phoenix and Tucson will be the first asked to make usage cuts after agricultural and industrial users (9).

The dwindling water supply in the major reservoirs of Lake Powell and Lake Mead have forced states, tribes, and other interest groups to negotiate new policies. The seven states that use the water are divided into two categories; the upper basin is Colorado, Utah, New Mexico, and Wyoming, and the lower basin is Arizona, Nevada, and California. In 2026 new rules will take effect to manage the river. As of spring 2024 the two basins are still struggling to negotiate the terms of the new rules. The upper basin has already made cuts and would like the lower basin to assume more responsibility for the decrease, while the lower basin is emphasizing the need for all seven states to decrease water use. Tribal groups are concerned their rights will not be protected (14).

Reclaimed water: Conservation Innovation

Reclaimed water is an impactful solution for a sustainable water future. Usually wastewater treatment plants expel their treated water into natural bodies of water, or groundwater. In the reclamation process the filtered water is sold to companies to use instead. Some of the uses include landscape or crop irrigation, watering golf courses and generating electric power (1). There are different grades of reclaimed water depending on how intensively it is filtered. More than 70% of reclaimed water in Arizona is treated to A or A+ class allowing for it to be used in scenarios where it is likely to come into contact with humans (1).

With modern technology we can easily filter waste water to the same standards as a drinking water purification plant. This means we could directly convert our wastewater into drinking water. This is called direct potable reuse (2). Arizona lifted the ban on direct potable reuse in 2023, and is viewing it as a potential solution for the future (3).

It is understandable that people may have concerns about direct potable reuse. It's important to understand that we already reuse wastewater for drinking water, but with environmental buffers in place. The common practice is to first dispel treated waste water into a lake, river, or aquifer, and then take water out of that body of water to purify it for drinking water (2). Direct potable reuse takes away this middle step.

Reclaimed water will likely become an even larger portion of Arizona’s water usage in the future as the Colorado River continues to decline. It is a promising technological solution for future water security.

Water Management: AMAS and Conservation Measures

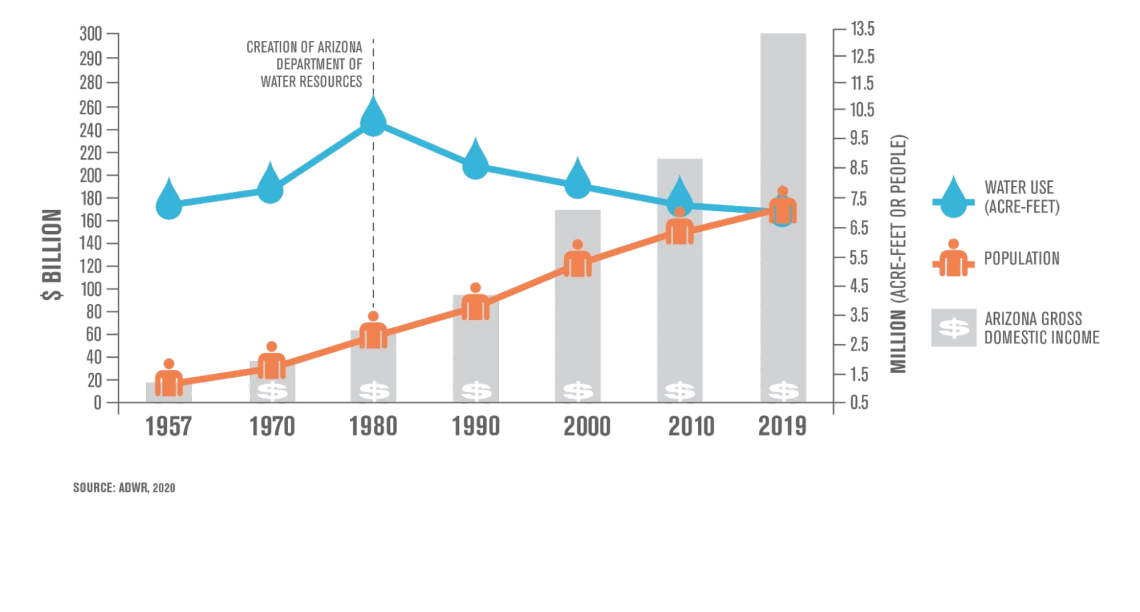

ADWR, 2020

Arizona’s water use reached an all time high in 1980. Arizona policy makers needed a plan to sustain the state's growing population and economy. Most major cities were relying on groundwater, but they were using it faster than it naturally replenished (5).

The 1980 Arizona Groundwater Code was passed to manage this important resource. It designated 5 Active Management Areas (AMAS) where 82% of Arizonans lived. In the Tucson, Phoenix, and Prescott AMAs the management goal is to lower water usage until the amount withdrawn is equal to the amount refilled annually. This is called safe yield. In the Santa Rita AMA the goal is to maintain safe yield. In the agriculture capital of Pinal County AMA the goal is to support farming as long as it is possible without harming other residents (13).

AMAs enforce policies that save water by regulating industry, agriculture, and municipal use. Through AMA strategy over 3 trillion gallons have been stored in formerly exhausted aquifers, an amount that could support the city of Phoenix for 30 years (13).

Areas outside of the five AMAs also rely on their aquifers. It is especially important for many rural towns. It would be challenging and expensive to transport water to every town in the state so rural residents usually rely on local sources like natural streams or groundwater from wells (7).

What Can Individuals Do?

Homeowners' largest water usage percentage is usually spent on landscaping. Growing grass and other non-native species in the desert is water-intensive. Desert landscaping can be beautiful and use less water than non-native grass, and can also provide a home for native pollinators. If watering the yard is necessary, do it in the evening when it’s less likely to evaporate because the air is cooler.

In the US the largest source of water use in the home is usually the toilet, with an average of 33 gallons per day. Leaks are another surprising source at an average of 18 gallons a day. Installing a low or variable flush toilet and fixing leaks are household changes that can save a lot of water, and also money (4).

Check out this calculator if you want to learn more about your own water footprint!

https://home-water-works.org/calculator

Sources

- Tucker, D., 30, G. C. O., 12, B. R. N., & 22, L. L. A. (2015, October 29). A win-win-win: Regulation, use, and pricing of reclaimed water in Arizona. Environmental Finance Blog. https://efc.web.unc.edu/2015/10/29/reclaimed-water-arizona/

- Environmental Protection Agency. (2024, January 11). Potable Water Reuse and Drinking Water. EPA. https://www.epa.gov/ground-water-and-drinking-water/potable-water-reuse-and-drinking-water

- ADEQ. (2023, November 2). Press release: AWP: Adeq. PRESS RELEASE | AWP | ADEQ. https://www.azdeq.gov/PR/AWP

- Indoor water use at home. Water Footprint Calculator. (2022, July 15). https://watercalculator.org/footprint/indoor-water-use-at-home/

- ADWR. (n.d.). Water your facts. Water Your Facts | Arizona WaterFacts. https://www.arizonawaterfacts.com/water-your-facts

- National Geographic. (n.d.). Aquifers. Education. https://education.nationalgeographic.org/resource/aquifers/

- Water for Arizona. (2024, January 19). Secure groundwater for rural communities. Water for Arizona. https://www.waterforarizona.com/priorities/secure-groundwater-for-rural-communities/

- Thompson, D., & Herman, V. (2020, April). scrhp_article_world_water.pdf. World Water.

- Person, D. (2023, November 29). A matter of priorities. Central Arizona Project. https://knowyourwaternews.com/a-matter-of-priorities/

- Bustillo, X. (2023, May 18). Arizona’s farms are running out of water, forcing farmers to confront climate change. NPR. https://www.npr.org/2023/05/18/1176657700/arizona-farms-running-out-water-farmers-climate-change-colorado-river

- Flavelle, C., & Rojanasakul, M. (2023, January 27). As the Colorado River shrinks, Washington prepares to spread the pain. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2023/01/27/climate/colorado-river-biden-cuts.html

- "Groundwater: aquifers, wells and circulation" by GRIDArendal is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0.

- ADWR. (n.d.). Active management area overview. azwater.gov. https://www.azwater.gov/ama/active-management-area-overview

- Estabrook, R., & Wertz, J. (2024, March 15). Colorado River states remain divided on sharing water, and some tribes say their needs are still being ignored. Colorado Public Radio. https://www.cpr.org/2024/03/15/colorado-river-states-divided-sharing-water-tribes-say-needs-being-ignored/