Faculty Feature: Beth Tellman

Beth Tellman, assistant professor in the School of Geography, Development, and the Environment, is one of two Udall Center for Studies in Public Policy Fellows supported by the Arizona Institute for Resilience (AIR) this year.

In this Q&A, Tellman talks about strengthening flood resilience and community rebuilding, using data to address injustices in flood mitigation infrastructure, and promoting a justice-centered approach to environmental challenges.

Tellman offers insights into the role of geographers as interdisciplinary facilitators and advocates for social and environmental justice, and she shares her vision for her Udall Fellowship, through which she aims to leverage satellite and geospatial data to drive policy changes that promote sustainability and justice for both people and the environment.

What inspired you to focus on issues related to water, and how do you see these challenges evolving in the coming years?

In 2009, while I was residing in El Salvador, Hurricane Ida destroyed many of the communities where I had initially planned to research fair trade coffee as a Fulbright scholar. Witnessing the devastation, I made a decision to shift my focus toward humanitarian efforts.

This shift led to the establishment of an NGO in collaboration with local community members. Our mission was to support flood resilience and assist in the rebuilding of the affected areas.

The events in El Salvador opened my eyes to a complex nexus of issues: informal urbanization, corruption, land change and climate dynamics that culminated in the loss of lives and livelihoods I saw in that event.

"In the era of climate change, our imperative is clear: We must adopt proactive responses that tackle the root causes of increasing flood risks and inequities. A justice-centered approach is essential for reshaping the rules and dismantling the structural inequalities that determine whom extreme events impact and how they impact people’s lives."

- Beth Tellman, assistant professor of geography, development, and the environment

We see similar stories play out in different places. In Libya, climate change exacerbated a storm that was bigger than it would have been on a non-warming planet. The city of Derna was vulnerable because it did not receive support for dam maintenance despite prior warnings from engineers. This vulnerability stemmed, in part, from the fact that in 2011, the U.S. and NATO effectively removed former Libyan ruler Muammar Gaddafi and dismantled the government without adequately supporting development, governance or reconstruction efforts.

Unfortunately, Libya serves as an illustration of both climate injustice — where a country with minimal emissions bears the brunt of adverse consequences — and vulnerability due to inadequate governance, largely resulting from Western intervention. It rhymes with the type of disaster colonialism that plays out in Puerto Rico: Severe storms in a changing climate strike a country where its colonizers have hindered investments in essential flood mitigation infrastructure maintenance.

Libya was the deadliest flood disaster in 50 years. For me, it's a reminder that flood adaptation is a social and political process, applicable from Libya to the United States. The critical question emerges: Who decides what infrastructure gets built and maintained, and for whom? I am interested in how we use data to support organizations that address injustice in flood mitigation infrastructure.

In the era of climate change, our imperative is clear: We must adopt proactive responses that tackle the root causes of increasing flood risks and inequities. A justice-centered approach is essential for reshaping the rules and dismantling the structural inequalities that determine whom extreme events impact and how they impact people’s lives.

Water-related challenges, such as heat waves and droughts, are hazards destined to intensify as the climate changes. Similar approaches that center on justice are required to adapt to those changing risks, too.

How do you see the role of geographers evolving in the coming years in addressing global environmental change and promoting social justice?

Geographers have long been working with human-environment relationships with a focus on global change concerns that prioritize human influences, experience and agency.

The call for interdisciplinary collaboration is growing stronger. Fields like ecology and hydrology are recognizing the significance of social sciences, while political science and economics are seeking insights from environmental change data to decipher human behavior. Geography can be a place to turn for frameworks of how to integrate BOTH human and environmental dimensions and their feedback loops. Geographers are key translators on large interdisciplinary teams facilitating the appreciation and integration of diverse expertise.

While geography traditionally plays a role in "spatial" analysis, the widespread accessibility of tools such as GIS, remote sensing software and R/Python packages for spatial analysis has somewhat diminished geographers’ exclusive role in this domain. Instead, I see geographers' unique role as interlocutors across and between disciplines, extending beyond academics to promote social justice.

How do you think new spatial analysis tools like satellite imagery and machine learning can supplement our understanding of environmental changes?

We have better tools such as machine learning and a wealth of data including an increased number of satellites that enable us to understand global-scale environmental changes with high resolution. In particular, the last five years have witnessed a surge in new commercial and public satellites, facilitating the mapping of changes at unprecedented spatial and temporal resolution.

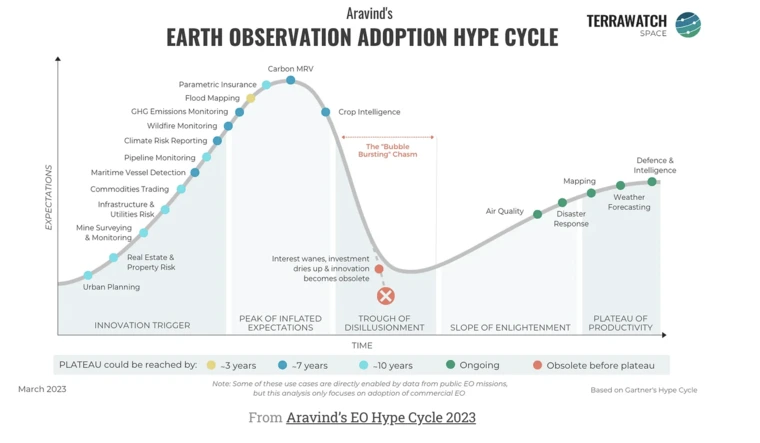

The Earth Observation (EO) sector is exploding and growing, both in academia and industry. However, it is important to acknowledge a hype cycle, as depicted in the figure below.

I agree with Aravind that the hype about EO data is larger than the reality of operational use in day-to-day decision-making, and EO has only really matured for weather forecasting, defense, and maybe air quality and certain disaster response applications. I work in flood mapping, and it's definitely at an inflated expectation phase right now. We have yet to see serious government and commercial decision-making operation-level adoption. Many of these applications will likely need another three to seven years or even longer to mature.

Indeed, many practical policy impacts, ranging from social vulnerability to developing national flood insurance programs, have come from geography. Hopefully, we continue to see climate and environmental justice push forth from all disciplines, with geographers playing a helpful role in making sure transdisciplinary knowledge and diverse ways of knowing are valued as we build transformative futures.

Can you tell us more about how you involve marginalized communities in your research?

There is a broad spectrum of how I involve communities in research.

At the most participatory level, I co-design research with community partners who secure funding to collaborate with us on research endeavors. This collaborative effort emerges from conversations and relationship-building spanning several months to years, culminating in developed research questions. This is the case of our project on Flood Justice in the Rio Grande Valley, where we directly fund community-based organizations and co-produce research with them.

At lower levels of involvement, I partner with government agencies such as the Bangladesh Flood Forecasting and Warning Center. While these agencies may not directly represent marginalized communities, they serve as field guides, facilitating on-the-ground discussions and fieldwork experiences and sharing data. This approach enables us to hear their stories of flood impact and ensure that the dynamics they describe are accurately reflected in our flood mapping efforts. We work with them to ensure what we produce is accessible and useful at broader governance levels, such as the country scale.

You recently received a Udall Center Fellowship. Can you tell us a little about your project for that?

The Udall Center Fellowship came at an ideal time in my career trajectory to reshape my global remote sensing research toward greater policy relevance in the borderlands region. I plan to use my time at the Udall Center to submit proposals to fund transdisciplinary flood justice work in Arizona and the borderlands region with existing and new collaborators.

As a fellow, I’m conducting applied research on flooding and land use change in the U.S.-Mexico borderlands. I am excited to be a part of the fellows program and receive mentorship on how to do policy-relevant research in the Southwest while engaging with other fellows working to mitigate vulnerability or using data science for social and environmental justice.

Ultimately, I hope to better leverage satellite and geospatial data to enact legal, regulatory, or procedural changes that could have a deep and long-standing impact to promote sustainability and justice for people and the environment.