Centering the Source of Water Knowledge:

Centering the Source of Water Knowledge:

Community-engaged research generates clean water solutions for all.

By Maria Arantes, AIR Communications Student Assistant | Dec. 7, 2023

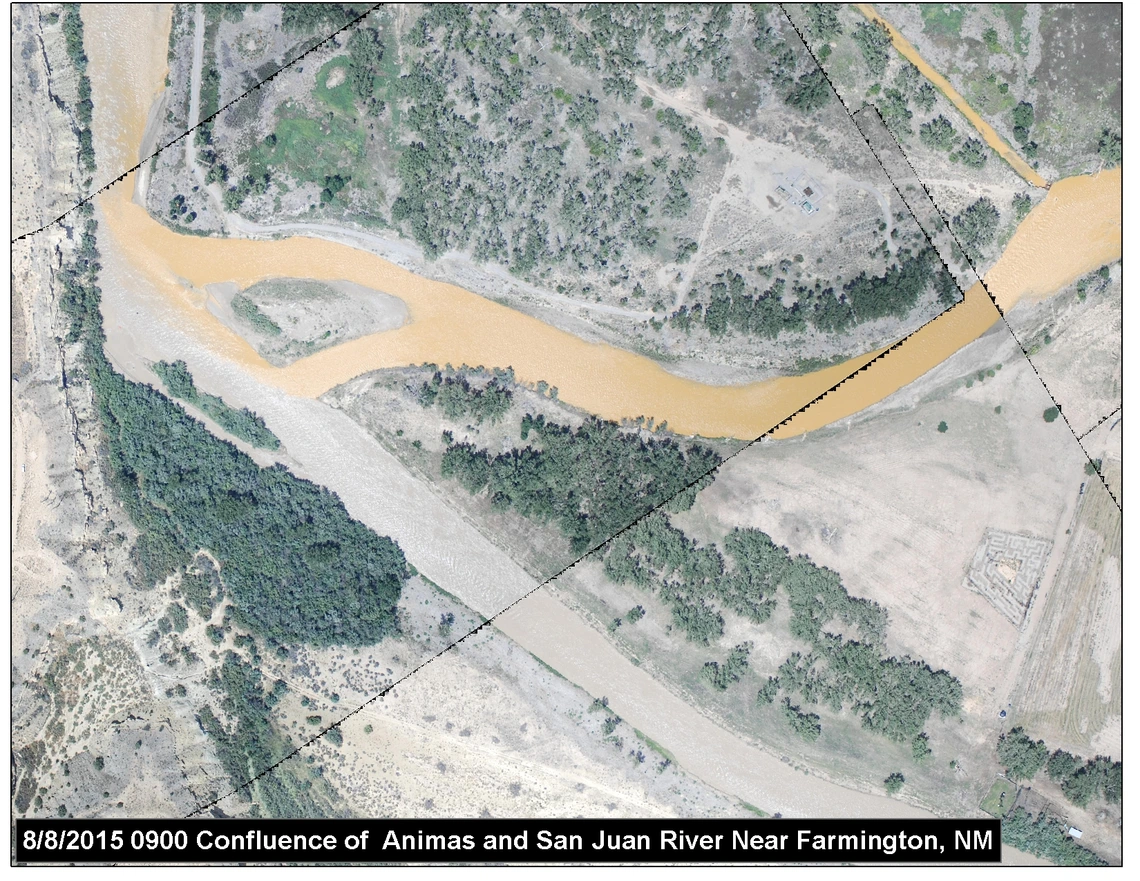

On August 5, 2015, the Gold King Mine spill released 3 million gallons of acid mine drainage into a Colorado creek, resulting in a catastrophic event that profoundly impacted the Navajo Nation, whose spiritual and physical lifeblood is closely tied to the downstream San Juan River.

The Gold King Mine Spill and its impacts on the Navajo Nation illustrate a pattern that reoccurs across Arizona and the United States: Environmental health risks are disproportionately placed on low-income or communities of color. These marginalized communities are exposed to environmental burdens, and they also experience additional socioeconomic challenges such as political isolation or information disparities.

Additionally, public authorities have historically imposed decisions on communities or viewed people as subjects rather than partners, sewing distrust across generations, said Paloma Beamer, Professor and Interim Associate Dean of Community Engagement at the Mel and Enid Zuckerman College of Public Health.

Recognizing the entwined connection between disproportionate contaminant exposure and public distrust, faculty members like Dr. Beamer, along with Dr. Karletta Chief, Director of the Indigenous Resilience Center within the Arizona Institute for Resilience, and Dr. Mónica Ramírez-Andreotta, Associate Professor of Environmental Science, are utilizing community-engaged research methods to connect with communities.

Paloma Beamer, Interim Associate Dean of Community Engagement, Professor of Public Health, and Director of the WEST Environmental Justice Center.

These methods follow an environmental justice framework and center the experiences and knowledge of local communities which, in turn, help identify research priorities, build trusting relationships, uphold self-determination and ultimately generate more accurate information to shape public health solutions, including those focused on water quality.

“The bigger picture is not that we need more policies, but that there's a lot of mistrust in the policies we currently have,” said Beamer, also Director of the WEST Environmental Justice Center and the Director of the Community Engagement Core for the Southwest Environmental Health Sciences Center.

Part One: Identifying the Research Question

After the Gold King Mine Spill, Diné community members had concerns regarding pollution of the San Juan River, which was receiving contaminated water from its tributary, the Animas River. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency conducted its own risk assessment to estimate potential recreational adverse health impacts from water sediment contaminants including arsenic, cadmium, lead and mercury. It found that the spill's contaminant levels were “not expected to cause adverse effects over an extended period of time,” according to the EPA’s response.

Focusing on recreational, agricultural or drinking water quality is a common scope for such risk assessments, Chief said.

However, in this case, it did not consider the full range of Diné interactions with the San Juan River, she said. At the request of the Navajo Nation, Chief, Beamer and a team of interdisciplinary researchers decided to quantify the holistic impacts of the spill on Diné-specific activities, focusing on the Navajo community's engagement with the river beyond recreation and farming to include cultural and ceremonial aspects and its impact on health.

Credit: Eric Vance/EPA

Credit: Eric Vance/EPA

Credit: U.S. EPA

Credit: U.S. EPA

Clockwise from top left: As water exits the mine, it flows into a system of four treatment ponds. The treatment ponds provide retention time to allow the pH to adjust. Here, lime is added to a settling pond to assist in the pH adjustment of the water prior to discharge to Cement Creek on Aug. 14, 2015. Discharge from the Gold King Mine shortly after it was breached on Aug. 5, 2015. Water monitoring taken in the Animas River near Durango, CO on Aug. 14, 2015. Photo of the confluence of Animas and San Juan River near Farmington, New Mexico taken on Aug. 8, 2015.

The Navajo community, including Diné researchers, community leaders, local health representatives, cultural and faith-based experts, and environmental agencies, led the research questions.

“We really made an effort to listen to the communities,” Chief said. “They were the ones to ask us for help. It wasn't us going into the community, it was because our extension agent on the Navajo Nation was asked all these questions from the farmers and the residents who were living there in that community at the time, right in the middle of all this that was happening.”

The extension agent then brought those questions to the Superfund Research Center, which had already been working on outreach and partnership building through training programs with the Tribal College.

Karletta Chief, Director, Indigenous Resilience Center, Professor & Extension Specialist, Department of Environmental Science

“We were really looking for the guidance and the lead of the community to guide our work,” Chief said. “The questions came from the community, we worked to develop a study that specifically addressed those questions, and then we worked with a cultural guide and mentor to make sure that we were trained on how to work with the community.”

Ultimately, the study observed decreases in day-to-day activities across livelihood, dietary habits, recreation, cultural and spiritual practices, and arts and crafts. Its timing during early fall — a pivotal period for harvesting and cultural festivities — meant it had acute cultural repercussions including a stark drop in the consumption of river-irrigated crops and participation in religious practices. Navajo interactions with the River decreased considerably, potentially intensifying trauma by affecting their ability to pass on teachings to future generations, Beamer said.

“What made the community feel more assured with our estimates was that they knew it reflected the reality of their activities and all their concerns they had shared with us about how they use the river," Beamer said. "It's about learning how to be humble and recognize that the community members are really the experts and that you're there to provide some technical expertise.”

Related Content

Community-engaged processes are central to effectively serving communities through research, Chief said. This is particularly crucial when working with marginalized communities, who often have lingering distrust toward entities that have historically exploited them. Building trust, Chief said, is extremely important and must be approached carefully, ensuring that community members are empowered with the necessary resources and support.

Universities can be a helpful actor in this process, serving as centers of learning where scientists act as neutral parties, utilizing research resources, tools, and outreach. In this context, universities emerge as neutral partners helping communities, Chief said.

"But I think what sets the University of Arizona apart as a university engaged with communities is our history of collaborating with marginalized communities, those along the border, tribal communities, and so forth," Chief said.

The San Juan River flows near Farmington, New Mexico.

Part Two: Community Empowerment

Mónica Ramírez-Andreotta, Associate Professor, Environmental Science

Aligning research with community concerns is just one component of community engagement research. Equally as important are questions regarding ownership and empowerment – who owns the information and resources generated by this work, and how do those empower the community?

Generating dialogue and bringing the voices of affected people to the center of the research process are vital to addressing challenges, said Ramírez-Andreotta, who integrates participatory methods into her environmental monitoring research and environmental health literacy efforts.

“By doing that, you strive toward structural change and see translation of research to action,” Ramírez-Andreotta said.

Ramírez-Andreotta integrates these principles into her work by partnering and having the research question stem from communities, training community members how to properly collect and measure soil, plant, dust and water samples to track the presence of toxins in their home and community gardens, and by maintaining ongoing bi-directional communication and data report back efforts throughout the research process to facilitate action.

Monica Ramírez-Andreotta discusses "Community-based Science for Justice and Action" at TEDxUArizona 2023.

For example, Gardenroots utilizes a co-created citizen/community science approach to evaluate environmental quality and potential exposure to contaminants from nearby resource extraction and hazardous waste sites. The project stems from community concerns and has involved over 100 trained community scientists who collect water, soil, plant and/or dust samples, co-producing relevant data and improving environmental health literacy in underserved communities.

Instructions provided in Project Harvest data sharing materials describing how to understand graphs that display sample results for various contaminants.

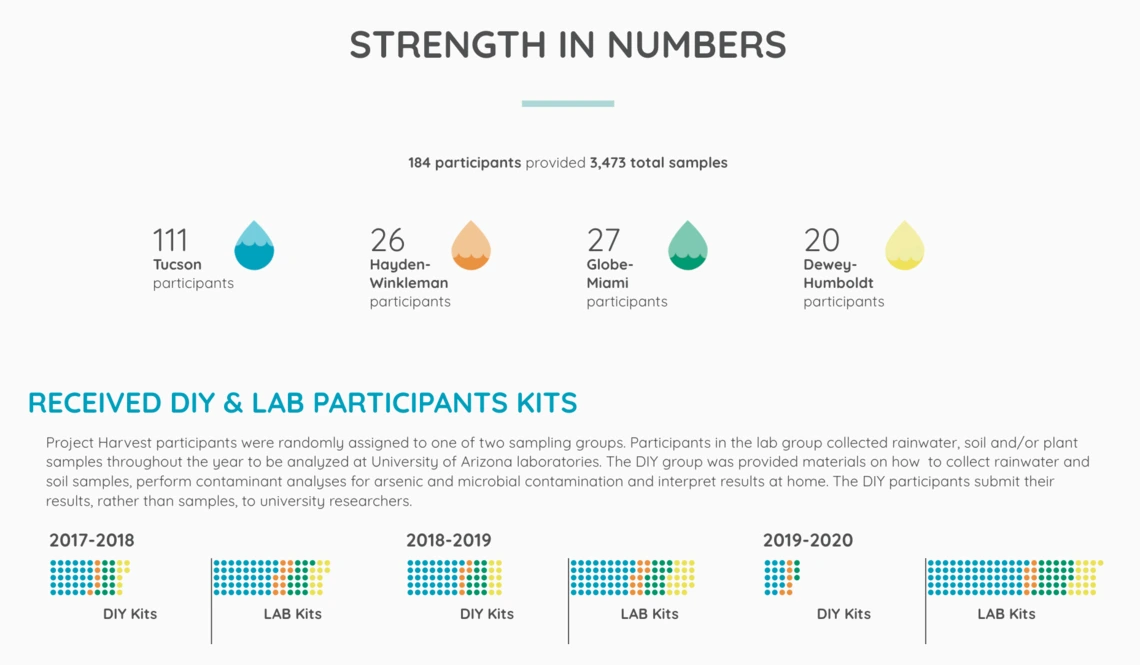

Another of Ramírez-Andreotta’s co-created community science programs is Project Harvest, developed in partnership with the Sonora Environmental Research Institute, Inc. and communities throughout Arizona. Using a peer education model, promotoras (community health workers) trained community scientists on how to properly collect environmental monitoring samples and together the community-academic team evaluated potential pollutants in harvested rainwater, as well as in irrigated soil and grown plants; essentially building capacity and individual and community-wide environmental health and data literacy.

“These efforts can nurture a new or renewed relationship with science, and the outcomes of co-created efforts can foster trust and action, support ongoing science engagement, set the pace for social transformation, and possibly provide the foundation for structural change,” she said.

Another example of community ownership is a project led by the Indigenous Resilience Center in partnership with the Navajo nonprofit Six World Solutions to pilot off grid water filtration systems on the Navajo Nation.

Many homes on the Navajo Nation are located in extremely rural areas without direct access to water systems, so when the pandemic struck and the stay-at-home orders were issued, the Navajo Nation Council reached out to Chief and her research team, inquiring if there was a way to develop systems that could provide clean water to homes. The trust established through prior projects, like the Gold King Mine Spill, was crucial to initiating this partnership, Chief said.

“It always goes back to listening to the people,” Chief said. “What do they need? What is appropriate? Do they even want these systems? And how can we make these water systems better?”

Karletta Chief and collaborators discuss their community-led project to provide water purification units on the Navajo Nation.

In response, the team focused on creating low-cost, low-maintenance, and easily operable water systems suitable for the nation. The vision, Chief said, is to have these systems produced and implemented entirely by the Navajo Nation.

“The ultimate goal is that these systems will be built by the Navajo communities and made available by Navajo communities so that they're benefiting the Navajo economy through jobs, through manufacturing production of these systems,” Chief said.

Part Three: Accessible Communication

A final important aspect of community-oriented research involves the effective communication of scientific knowledge.

Access to information is crucial for rural communities that are either concerned about or that struggle within ongoing water contamination, Beamer said. Understanding what contaminants are present, along with the most effective treatments for those contaminants, are both key pieces to effectively addressing the issue.

“It's about learning how to be humble and recognize that the community members are really the experts and that you're there to provide some technical expertise.”

However, Beamer’s research has found that people may turn to home water treatments or bottled water to address their water contamination concerns, but those strategies may not match the actual challenges they are experiencing; not all home water treatments, for example, filter out the same contaminants, and some water sources are less or more contaminated than others.

That’s why, Beamer said, "increased educational outreach on contaminant testing and treatment, especially to rural areas with endemic water contamination, would result in a greater public health impact.”

Related Content

One aspect of environmental justice is to follow a community-first communication model and ensure the results and information are available in multiple formats and the languages spoken by the partnering communities, Ramírez-Andreotta said. This requires researchers to think creatively about information design, visual communication and nontraditional forms of communication to share information in ways that empower community members.

Ramírez-Andreotta’s projects emphasize data visualizations and artistic media to help participants understand and make informed environmental decisions. Dr. Ramírez-Andreotta incorporates artistry when communicating to the public to "ensure that the data is presented in a way that's digestible, accessible and useful to create the change that the community scientists want to see for themselves, their community and beyond," she said.

All 2.5 years of Project Harvest data were co-designed and visualized in a variety of formats, including in Spanish and English, to make in the information accessible for a wide audience.

A key partner in many of these communication and outreach efforts is the Cooperative Extension, a unit within the University of Arizona tasked primarily with community engagement.

As an extension specialist, Karletta Chief communicates her research findings not only to the scientific community but also to the public. She utilizes extension publications, videos, fact sheets, informal meetings, workshops, seminars, and educational sessions. She is conscious of how her findings benefit the people of Arizona, influencing behavior change and improving the economy.

"Our primary goal is to relay information back to the people," Chief explained. "This doesn't happen only after we get results; the communities are kept informed throughout the entire research process. We are constantly communicating, ensuring that the results are presented to and approved by the community members before they are shared with the broader scientific community."

Related Content

In the Gold King Mine Spill project, Chief and Beamer’s research team collected a vast amount of data that required extensive analysis. To keep everyone informed, they created presentations to explain the process and the reasons for the time it took.

“We invited community members and tribal leaders to our labs, giving them tours and showing them our work,” Chief said. “This process of communication helps build trust, gather feedback, and forge stronger connections."

Chief and her team, through this approach, established the Indigenous Food, Energy, & Water Security and Sovereignty (Indige-FEWSS) program. In this program, students learn about ethics, cultural immersion, science, communication, and the nuances of working within communities to decolonize research.

"Now, through the Indigenous Resilience Center, we are sustaining aspects of Indige-FEWSS, which even led to the creation of a Phd. Minor in Indigenous Food Energy Water Systems," Chief added.

Water is life, and knowledge is power.

Researchers like Ramírez-Andreotta, Chief and Beamer are adopting community engaged research methods to center, serve and empower communities.

“The focus is to help the community, where they are leading the work because of all of this distrust that has happened in the past,” Chief said. “When we're doing community engaged research, it's not really about the research per se. It's really about what the community’s questions are, and how we can be of service to answer those questions.”

This approach fosters a more accurate understanding of health risks and solutions, integrating eco-cultural dimensions and augmenting self determination by involving them in research and decision-making processes, ultimately changing the way we practice and communicate science.

For Dr. Chief, research, education and outreach should be centered around service, and to that end, she advocates for focusing academic research on assisting the community by allowing them to lead the work and address their specific concerns. Many communities of color have experienced trauma and therefore may view outsiders within that scope of history, making it particularly important for researchers to recognize how they fit into that context, she said.

“You don't have to be Indigenous to work with Indigenous communities,” Chief said. “It's really about how much you're willing to learn, to listen, and to take the time and to think about your own positionality where you're coming from.”

Opening up science and research efforts to wider participation and partnership provides a multitude of advantages, from generating more relevant research questions to innovating more effective solutions.

"Getting more people involved in science is not solely about getting more people graduating with PhDs, but rather providing space to more people to generate knowledge and become part of the scientific conversation,” Ramírez-Andreotta said.