Faculty Feature: Stacey Tecot

Stacey Tecot is an associate professor in the School of Anthropology and the director of the Laboratory for the Evolutionary Endocrinology of Primates. She studies how behavior and physiological strategies help individuals cope with ecological and social change, currently focusing on the evolution of cooperative infant care and bonding in a range of species.

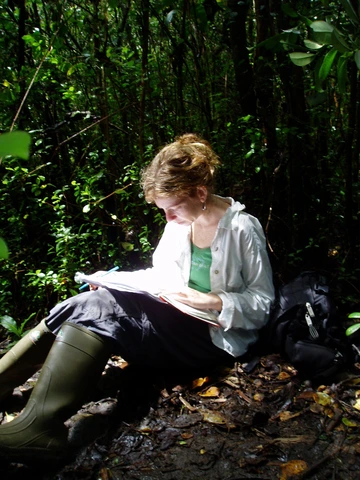

Dr. Tecot conducts her fieldwork in Madagascar, where she is collaborating with tourists and research guides on a storytelling project aimed at preserving and sharing ecological knowledge.

In this Q&A session, she sheds light on the storytelling project's origins, the profound encounters she had in Madagascar, and the potential contributions her research can make across various domains of human understanding.

Can you tell us more about the storytelling project you're working on with tourist and research guides in Madagascar, and how it's helping to document and disseminate ecological knowledge?

This project was in the works for a while, but I struggled in securing funding for it. As a result, I worked on it slowly during my spare time while focusing on other projects.

The initial idea came to me while I was in the forests of Madagascar, listening to research guides share captivating stories about the local wildlife. The generation of guides that taught me when I was a grad student was aging, and I thought that documenting that knowledge for them to share with their families and communities would be helpful. Moreover, I hoped that this project would highlight their expertise in a system where foreigners and people with advanced degrees are often the ones who get credit for the work. Ultimately, the goal of the project was for the guides and research techs to inspire the next generation of ecologists and biologists in Madagascar.

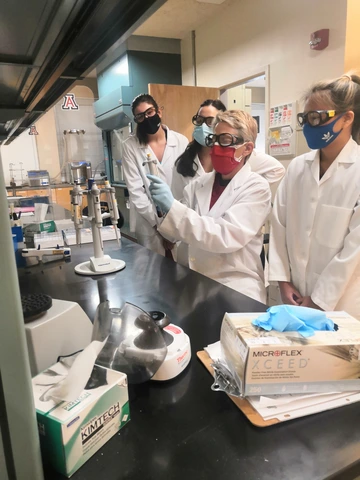

When the pandemic hit and all research and tourism in the forest stopped, I received a School of Anthropology faculty research grant. This grant meant to support new research directions resulting from pandemic restrictions, and I collaborated with two graduate students from UArizona and the staff at the Centre ValBio research station in Madagascar. Together, we recruited research and tourist guides, who were experts in the local plants and wildlife, to participate in the project.

To gather the necessary information, we conducted semi-structured interviews with the research guides over Zoom. These interviews focused on their personal experiences growing up in and around the park, as well as their work within the area. We also asked them about what they believed was crucial for everyone to learn and know, how they would utilize research funding, and their aspirations for future generations. In total, we recorded 22 hour-long videos.

To streamline the content, we partnered with an organization called ExplorerHome Mada, which helped us edit the videos down to 5-10 minutes each. All the videos are in Malagasy with English subtitles. We are currently nearing completion of this editing process.

Our plan is to showcase the videos during one or two events in Ranomafana and publish them online, along with biographies written by each participant. Furthermore, we aim to broadcast the audio from the videos on several radio stations in Madagascar. Lastly, each participant will receive a copy of the video to use as they please.

Can you share a specific experience or moment from your fieldwork in Madagascar that has had a significant impact on your research or personal perspective?

Reflecting on my nearly 25 years of experiences in Madagascar, it is difficult for me to pinpoint a specific moment that stands out, as the entirety of my time there has significantly shaped my present self. However, one particular encounter remains etched in my memory.

Around 10 or 15 years ago, before commencing a new project, I visited the regional director of Madagascar National Parks. On this occasion, I planned to conduct research in a familiar area where I had previously worked for a couple of years. We had knowledge of the animals, mapped ranges, marked trails, and more. To my surprise, the director presented a different location on the map, one where I had no prior experience and was unsure if my desired study species resided. I explained my reasons for selecting the site I had and the restrictions imposed by my funders. Ultimately, after a nervous conversation, the director granted permission for my study.

In retrospect, I fully understand and agree with his perspective. Despite our theoretical and practical intentions, it is crucial to engage in discussions with on-the-ground experts and heed their invaluable insights.

Collaboration lies at the core of the teams I work with in Madagascar, which comprise both local experts and individuals with varying levels of expertise. Some of the local team members have spent decades working in the forests, possessing a wealth of knowledge. Throughout our research process, knowledge exchange and training occur within the entire team, including myself. The research technicians, as designated by the research station, actively participate in every aspect, from method development and selection of study groups to data collection and publication of results.

I prioritize sharing my work with local NGOs and Madagascar National Parks, submitting proposals beforehand. I also aim to have more face-to-face meetings with park officials and research technicians while in Madagascar, but unfortunately, as we’ve seen over the last few years with the pandemic, sometimes that is not possible.

In the absence of in-person conversations, I have found solace in this storytelling project that enables me to understand local concerns and interests, thereby facilitating fundraising efforts for research in those specific areas. While it may require additional time, resources, and trips, impactful research necessitates collaboration, consultation with local experts, and a steadfast commitment to serving local communities.

The challenges and complexities of research extend beyond theoretical and practical considerations, encompassing the intricate relationships between scientific exploration, local communities, and the environment. By valuing the input of local stakeholders, we can foster a genuine collaboration that respects their expertise, addresses their concerns, and ultimately contributes to more meaningful and impactful research outcomes.

How do you see your research on the evolution of pair bonding, infant care, and monogamy contributing to our understanding of human relationships and social behavior?

I am fascinated by the various ways individuals live and interact with others, whether it involves raising babies, reproduction, or simply spending time together.

Among primates, social behavior plays a crucial role, and extensive research has revealed the significant health benefits of cooperation and socialization. Exploring the diversity of these strategies, along with how they are influenced by evolutionary history and environmental changes, provides us with valuable insights into the incredible diversity of human populations around the world.

One aspect of my research focuses on lemurs and examines the hormonal changes that occur in non-pregnant family members when they are in the presence of an expectant female and later when they care for an infant.

By studying these changes, we can gain a better understanding of how a community has evolved to contribute to infant care and transition from a sole focus on pregnant individuals.

We are also interested in investigating how lemur fathers and older offspring influence pregnant females and their reproductive outcomes. It is important to recognize that a pregnant individual does not exist in isolation, and everyone they interact with can potentially have a lasting impact on them and their infants.

We are aware that environmental stressors, as well as those who create them, can influence pregnancy outcomes. However, my research also explores the positive ways others can contribute to reproductive outcomes. Understanding these dynamics can help us comprehend the complex web of relationships and interactions that shape the reproductive success of individuals in a community.

By investigating the interplay between social behavior, environmental factors, and reproductive outcomes, we can deepen our knowledge of the intricate mechanisms at play in primate societies, including our own.

You’ve discussed the importance of collaboration and uplifting local voices when doing research in a foreign area. How have you integrated ethics into your animal research as well?

After graduating college, I embarked on a job as a research assistant that ultimately forced me to deeply question the ethics of working with animals. It was during this pivotal moment that I realized the importance of conducting research that would be noninvasive, respecting the well-being of the subjects I studied.

This realization guided my subsequent search for graduate programs and became an unwavering principle in my own research endeavors. This pursuit was not without its challenges; I encountered resistance in securing funding for my dissertation research because many doubted the reliability of measuring cortisol in feces, a method that has now become commonplace. Undeterred, I focused on developing noninvasive techniques for monitoring health and physiology, including innovative approaches like utilizing photographs and facial recognition for individual identification rather than conventional trapping and collaring methods.

Reflecting on my experiences, I have come to understand the critical importance of defining my own ethical boundaries when interacting with the subjects of my research. The distressing encounters I witnessed underscored the need for a thoughtful assessment of the risks posed to animals against the potential benefits of the research I conducted. Whether it be through behavioral observations or other methods, I now constantly evaluate the significance of my research and its contribution to the well-being of the animals involved. This profound lesson continues to shape my work, serving as a constant reminder to ensure that my research always remains in service to the subjects themselves.